Why I made "The Ultimate Weekend" BMX freestyle video in 1990

No one made the BMX freestyle video I wanted to watch in the late 1980's, then cheap video equipment came along, so I tried to make that video myself

A photo I took of the last VHS video box I had of The Ultimate Weekend. My mom had one copy stashed away, probably unwatched, for over 20 years. The title is at the top, so it would show up in a rack at a video store. It’s in a black and white box because I did the box art myself, and I sucked at graphic design. It’s a Xerox art negative of a Mike Sarrail photo, Keith Treanor blasting over John Povah’s raised hand at the Ocean View High jump. I bought music from The Stain, a punk band, and group of very talented studio musicians, from Toledo, Ohio, so I gave them props on the cover. Here’s the link to the video:

The Ultimate Weekend- 1990- shot, produced, and directed by me (Steve Emig)

Yes, this YouTube version is rough, made from a 25+ year old VHS tape that was watched many times. The audio sucks, but that’s the only version of my video that I have access to now. I lost the master tape in a move in 2008, and all of my personal copies before that. This is the video project I’m writing about in this post. This post is about taking on a big (to you) creative project that you’re not sure you can actually finish. I’m not saying I made the greatest BMX video ever or anything. Finishing the project of producing this video was a big personal leap for me, and this post is about why I decided to do it.

BMX freestyle changed the course of my life, and gave me a direction to head in, when I exited high school. That was in Boise, Idaho in 1984. I got serious about BMX riding in a trailer park in 1982, and managed to stumble into the BMX industry by 1986, at age 20, thanks to a zine I published. The zine led to a magazine job, which lead to editing a newsletter and contest roadie work for the American Freestyle Association. That led to a chance to produce low budget videos, which led to a job at Unreel Productions, Vision Skateboard’s video company. There was no big plan, one job led to another.

By late 1989, the BMX industry had “died,” and the 1980’s skateboard wave was beginning to crash. Unreel Productions, where I worked, was dissolved in January 1990, as the country headed into a long recession. I was moved to the main office, and I sat in a room in Vision’s main building, bored out of my skull most of the time, for six months. I had a steady paycheck, though. Sounds like a dream job to many, but it drove me nuts. I like to be busy doing stuff. I had to figure out what to do next.

BMX freestyle, in its first, 1980’s, wave of popularity, was all about magazines. We read the news, which was three months old, in magazines. We saw the new tricks in still photos in magazines. You can check out scans of the old BMX magazines here, to see what I mean.

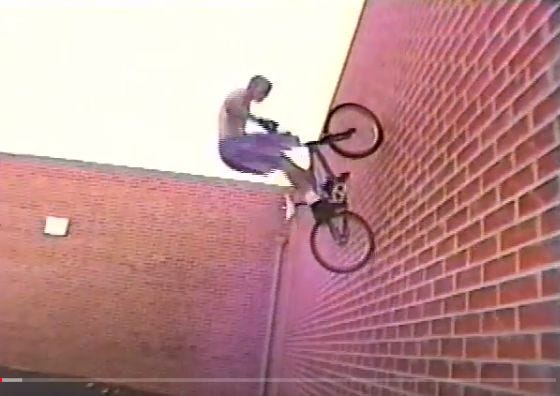

Young, hungry, and a recent New Jersey emigrant to Huntington Beach, here’s Keith Treanor blasting a big fakie wall ride in Garden Grove, California. He’s launching off of a four foot high launch ramp, onto the back of a shopping center. I like the way the mortar lines in the bricks give a perspective in this shot.

There were BMX freestyle videos in the 1980’s, but they were initially either made “Wayne’s World style” using Public Access TV equipment, or the BMX industry companies hired industrial video production companies to make a video. High grade video equipment cost a lot in the early 1980’s. Hiring a production company was really expensive, and while those people knew how to make technically good videos, they knew nothing about BMX freestyle. They tended to do these projects documentary style, which led to videos like the BMX Action Trick Team video, Rippin’, which came out in 1985. Rippin’ was a very well shot and well produced video for 1985. R.L. Osborn and Ron Wilton were great riders of that era. But the video is really boring after 3 or 4 views. That’s not the riders’ fault, it was that hungry BMX freestylers wanted to see more action and less set-up and day to day life stuff, in a video that cost $30 plus shipping. The problem was the format, and Rippin’ lost a bunch of money. There just wasn’t enough riding in it. There was no way to know that in advance, and it became a costly lesson learned.

The same year, rival magazine, BMX Plus! put out Freestyle’s Raddest Tricks, and took a somewhat different direction. It’s still a form of documentary video, but this video is faster paced, narrated in part by BMX freestyle pioneer, Bob Haro, as well as BMX Plus! editor McGoo and photographer John Ker. This video had more top riders, and more actual riding, because of it’s faster paced format. Freestyle’s Raddest Tricks sold well, and led to two follow-up videos by BMX Plus!.

This was the first BMX video I forked out $35 for, and that’s a lot when I was working for $3.25 an hour at Pizza Hut. I watched it 7 times the day I got it, twice while actually balancing on my bike in the living room. Really. I was that big of a dork. But, it’s still pro riders in full uniforms and helmets, even for flatland, and they’re riding in odd places like the beach bike path and the tables at the Venice Beach pavilion.

By 1990, the main BMX freestyle videos I had watched were Freestyle’s Raddest Tricks, GT Bikes first video, GT-V, and the Australian BMX movie BMX Bandits, starring a young redhead actress named Nicole Kidman. BMX Bandits, from 1983, was on heavy rotation on HBO in the late 1980’s, so a lot of us watched it there multiplie times. It was one of those movies often showing on Saturday mornings, when we were, bored, hung over, or just had nothing better to do. At Unreel Productions, they put out Freestylin’ Fanatics in 1989, which was better, but still didn’t represent what my friends and I were out doing on our bikes every day. Those videos, and the raw footage from contests shot by Unreel (sinced I worked there), were the videos I watched a lot, as an avid rider in that era.

Also in that era was the movie Rad, the bike messenger movie Quicksilver, which had a jam session scene, Eddie Roman’s self-produced, epic, no budget BMX/kung Fu, movie, Aggroman, Don Hoffman’s skatepark contest videos (and public Access TV shows), and Mark Eaton’s first couple Dorkin’ in York videos, a long with the Curb Dogs video. The Curb Dogs video, made by a pro video producer who had great distribution but not-so-great production values, along with the Dorkin’ videos, actually came closest to where BMX (and all action sports videos) were eventually headed, once more of us riders started making our own videos.

I showed this long, rolling shot of Red doing a hitchhiker to actual TV industry video editors in L.A., and they couldn’t figure out how I got these close-up shots that moved around the rider. Experienced TV guys had never seen video footage shot while the cameraman was riding a skateboard. These type of shots are something the action sports world taught Hollywood. Now these type of shots can be seen in lots of TV shows, commercials, and movies.

As the initial, 1980’s wave of popularity for BMX freestyle was peaking, something else was happening. A new type of video equipment was coming out. In the big gap between consumer VHS and broadcast quality video gear, new prosumer gear came out and began to drop in price. S-VHS cameras and VCR’s, along with Hi-8 cameras, got within the price range of average people. I bought an S-VHS camera for $1,100, which was actually one of the cheaper ones out, in late 1989. I started goofing around, shooting a little footage here and there before I got serious about actually producing my own video.

Us Unreel Productions employees knew things were getting dicey at Vision, our parent company, as the skateboarding wave began to fade, but the dissolving of Unreel still caught most of us by surprise. As the lowest paid guy who could work most of the equipment, I was one of two people kept on, and we soon got moved into the Vision main office building in Santa Ana, California. Soon the other person found a “real” TV job in Hollywood, so I was sitting in the office alone, without much to do. Once ever week or so, the owner of Vision would have a small project for me to do. As the Southern California rainy season was drawing to a close in the spring of 1990, I decided it was time to produce my own BMX freestyle video. That was something I’d had in the back of my mind for a few years, but I was not even remotely sure I could actually pull off.

I started shooting footage with my S-VHS video camera on the weekends, with whatever riders I was around, wherever we went. I had already produced seven BMX videos, six for the American Freestyle Association in 1987, and I produced and edited one for Ron Wilkerson at 2-Hip in 1989. I was also around when Unreel made Freestylin’ Fanatics. I had almost no say in how that video was made. That was part of my inspiration. I wanted to make a BMX freestyle video that showed real, everyday riding, and more importantly had fresh, up-to-date footage. BMX freestyle, particularly street riding, was progressing incredibly fast at that point, and no one was really documenting that progression very well.

In a previous post, I wrote about the two great questions that lead to cool, creative projects. In this case, my question was, “Why doesn’t someone make a BMX video with real, recent, riding? No motocross-style leathers or helmets while riding flatland. Real street riding at real street spots. A bunch of different riders with different styles, doing different types of riding. No one was making the video I wanted to watch every day before I went out to ride, so I thought, “Aw hell, I’ll make it myself.” A lot of really cool projects start out that way.

I was standing on top of Dan Hubbard’s quarterpipe, shooting footage of Todd Anderson and Dan doing airs, when Jeff Cotter did a pop tart a couple of times in the parking lot below. A pop tart is a jump up off the pedals and handlebars, straight up to a bar ride, standing on the handlebars. So I just shot down at Jeff doing a pop tart, accidentally getting a different angle at a really progressive trick for that time. Yes, he made it.

I started simple, just shooting footage of different riders every couple of weekends. Then, as I started riding with the same guys more often, we started hitting different spots, visiting different riding spots, going to places that hadn’t been in the few videos out at the time. I shot BMX freestyle footage focused around the Orange County area in that spring and summer of 1990, the year after BMX freestyle “died.” The money had drained from the sport, the posers had all moved on to pose elsewhere. What was left was the hardcore riders, and even many of the pros didn’t have big sponsors then, some had no sponsors at all. We were riding for the love of riding, and progression was happening fast, particularly in street.

As I got deeper into the project, and footage, and log sheets of that footage, were piling up, I asked myself, “What’s the point of a BMX freestyle video?” I actually spent quite a while thinking about that question. My answer was, “A BMX video should make you want to go ride… right now.” The point of watching a video was to get off the couch, and get psyched to head out and ride, immediately, and push our individual limits. I made the video that I thought needed to be made in 1990, when almost no “real riding” videos existed.

For people today, whether making an action sports video, or any other kind of creative projects, the continuing question is, “What do you think really needs to be made NOW, in today’s world?” That answer differs for everyone, and for each type of creative activity. But the basic process of having ideas, sorting them out, and making the decision to actually follow through on a big project (for your skill set), stays pretty much the same. The technology you use will change over time, and for different projects. But the mental process of deciding, committing, and then getting to work and actually finishing the project, stays much the same. That’s the point of this post. Is there a big project you’ve been thinking about? Is that project worth committing to?

I love this shot, and that’s due to Dan Hubbard’s choice of the location, to shoot his trick team, in a beach parking lot north of the Redondo Beach Pier. At the shoot, I walked up to the sidewalk above the parking lot, about the same height as Todd Anderson’s airs, and shot a long but wide shot. That angle and length of shot, blurred the skyline of Palos Verdes in the background, with the ocean below. This angle is unusual, and made for a cool group of shots visually.

In the middle of October, 1990, I finished editing The Ultimate Weekend. The “premiere” was showing it to Keith Treanor, the star of the video, in my living room. There was no big party or media hype in those days. I worked with a small surf and skateboard video distributor to sell the video. He sold about 500 copies over a few months. I spent about $5,000 of my own money making this video, and made about $2,500 back. Financially, it was a failure.

Nearly all the serious riders in BMX freestyle in 1990-1991, saw this video at some point, because there were so few BMX freestyle videos out then. This was the cleanest, and best edited, rider-made video when it came out. If nothing else, I showed other riders, “Hey, we can make pretty decent videos ourselves.” I wound up getting a lot of “first on video” shots, and showed things like mini ramps and the Nude Bowl, which hadn’t appeared in BMX videos before.

The Ultimate Weekend had some impact on the sport, it showed a whole lot of different riders, seasoned pros and young amateurs, riding all kinds of ramps, dirt, street, and flatland. Most important to me, I proved that I could actually make a BMX freestyle video on my own. That was huge, personally. I had what was a really big idea, for me, at that time. I made that idea happen. Yes, I did get a couple more video producing jobs after making this video.

The video was innovative, because so few riders had made our own videos at the time. I put the work in, and got the video finished and distributed, to some degree. The Ultimate Weekend was a “proof of concept” project, not just for me, but for other BMX riders as well. So that’s why I spent nine months, and $5,000, making this video, way back in 1990. I’ll ask you, again… do you have any big projects in the back of your mind? Is one of them worth making happen? Only you can answer that question.

There are no paid links in this post.