The Wonderful World of Zines

Publishing my first zine turned me from a daydreamer into a doer, that's when I began to actually act on my creative ideas...

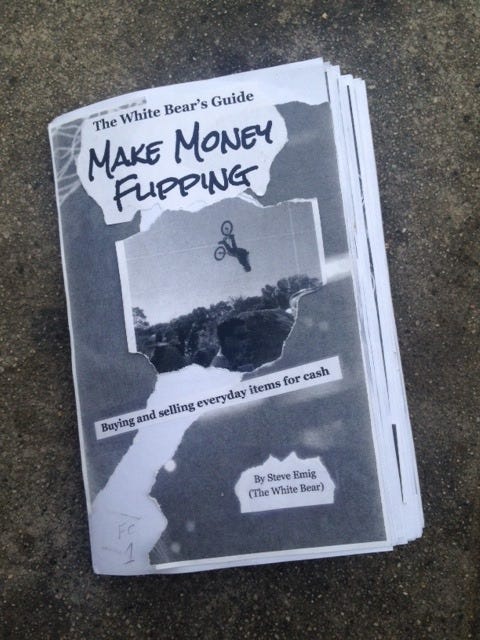

This is a zine I wrote about a year ago, mocked up, but ended up publishing as an ebook to my few Patreon supporters. I’ve lost all my previous zines, my own, and others I collected back in the day, mostly when I lost my storage unit in 2008, when I moved to North Carolina. I lost all my creative work in one fell swoop in that move, much to my dismay.

For any of you not familiar with them, a zine is a small, self-published booklet of prose, poetry, art, collage, or anything else you can photocopy. The word zine is pronounced “zeen,” as in magazine. Their history goes back throughout post-Gutenberg history. Thomas Paine’s “Common Sense,” which helped spark the American Revolutionary War, is usually described in history books as a “small, self-published pamphlet.” That was a zine, for its time period. There were also self-published little booklets of early Sci-Fi fan fiction, back in the 1930’s, another American era of zines, in today’s terms. In the late 1950’s and 1960’s, in the era inspired by beat poets and the folk music revival, some people self-published poetry, ideas, or short stories in “chapbooks,” another form of zines.

But the real surge that sparked the modern zine movement was punk rock of the mid 1970’s. Early in the punk culture, “Do-It-Yourself” became a rallying cry, and the DIY ethic emerged. No record company would record punk bands’ music, so bands learned how to record and put out their own records. No music magazine covered early punk shows, so punk fans shot their own photos of shows, and began to publish “fanzines,” homemade little magazines, usually copied on the Xerox copy machine at mom or dad’s office, after hours, when no one was around. In time “fanzines,” just became referred to as “zines.”

Zine publishers began to cover the punk scene in their city or region. They started trading zines with each other, interviewing their favorite bands, and talking about the new records coming out, and gigs coming up. As the late 1970’s rolled into the early 1980’s, other zines emerged, in other growing subcultures, like skateboarding, BMX, feminist/Riot Grrrl culture, environmentalists, and other underground scenes. Zines became a subculture to the subcultures. Zine culture itself became a thing. Maximum Rock n Roll started as a zine. In the 1990’s, Giant Robot magazine started as an Asian pop culture zine. Then there was Factsheet 5, a magazine that listed thousands, yes, thousands, of individual zines, with bios, contact, and subscription info. The best look at zine culture that I’ve seen is the documentary, $100 and a T-shirt (there’s 45 minute full version of this documentary somewhere). There was even an unofficial zine theme song, “Flagpole Sitta” by Harvey Danger, which mentions zines.

Personally, I first heard of zines in one of the early issues of FREESTYLIN’, the first BMX freestyle magazine. Editor Andy Jenkins was a huge fan of zines, punk and skateboard zines mostly, at that time. He published one himself on the down low. He wrote about zines in one of the first few issues of FREESTYLIN’, which first came out in the fall of 1984. I was a hardcore BMX freestyler in Boise, Idaho, at the time, and I liked shooting photos, though I only had a cheap, Kodak 110 camera. BMX freestyle was just turning into a sport then, and most people had never heard of it. I was the only BMX freestyler in my high school of 1,200 kids. There were about 8 punkers, and 2 or 3 skateboarders. All of those things were “fads,” really new, and not popular at all, in Boise at that time.

As was natural for me then, I thought about the idea of a zine. I sketched out the front page of the zine I thought about doing. I pondered what it should cover. But I didn’t make one. At that time, at 18 years old, and recently graduated from high school, I was a big day dreamer. I had all kinds of ideas. Great ideas. But I didn’t act on them. That’s the main point of this post. There are a lot of people with the urge, the drive, to do some kind of creative work. They secretly want to paint pictures, make music, create video games, make a documentary about something, or whatever. But these people, probably millions of them out there, maybe you, reader, don’t act on their “great” ideas.

As a kid, originally growing up in a series of towns in working class Ohio, I heard adults sit around and talk about great ideas all the time. “We should invent a new car that gets 60 miles to the gallon.” “We should build a hot rod in the garage.” “We should buy a piece of land out on a lake and build a log cabin to vacation in.” These were adults, many blue collar factory workers, or sometimes engineers like my dad. My dad, and many of his friends, wore white dress shirts and ties to work, but had a blue collar mentality, from their days suping up their Ford T-Birds and Chevy Corvairs, in the 1950’s and 1960’s. They had all kinds of good ideas. Pulling great practical jokes on an asshole boss was another thing they dreamed up ideas about, on a regular basis. That’s what working people did after work in those days, the late Industrial Age. They sat around, had a couple of beers usually, and talked about all the things they’d “like to do someday,” if they ever got the time and money. But, by and large, they never acted on those ideas. To me, dreaming up big ideas, and never doing them, was just normal life.

As kids in the 1970’s, that’s what we did, too. We wandered around the woods, or along a creek, after school. But we weren’t kids wandering a creek, we were great hunting guides in Canada, or we were pirates looking for treasure, or we were the first explorers in the wild jungle of some unexplored part of Africa. We were always pretending to be something other than what we were. Except we never pretended to be factory or office workers, as kids. That never seemed appealing, after hearing our parents, and other adults, complain about their jobs all the time.

In third grade, at Lincoln elementary, in Coshocton, Ohio, my class was on the third floor of an old school building. There were huge staircases from floor to floor. Between the second and third floors, there was a big landing, with a high backed bench, under tall windows. When we got in trouble in class, we’d often get sent down to “The Bench” to work on our homework. I loved that. I could stand up on the bench, stare out the huge windows, and just think. Imagine. Daydream. I would stand there and dream about some great adventure I would go on some day, when I grew up. I started getting in trouble on purpose, just so I could go daydream on The Bench, and not have to listen to the teacher talk about whatever boring thing we were learning at the time.

So, in Boise, at 18, I thought about making a zine, but never actually made one. I didn’t have money to go to college, and worked a restaurant job at night, and lived with my family. My dad got laid off that spring, in 1985, and he soon found a job in San Jose, California. We grew up moving almost every year, for one reason or another, so we knew another move was coming soon. My dad moved to San Jose, and started work. In June of ‘85, my mom and my sister moved there. I had a summer job, as manager of a tiny amusement park, called The Fun Spot. I rented a room at my best friend’s house, and worked the summer in Boise. In late August, when my job ended, I packed up my gigantic, 1971 Pontiac Bonneville, and drove to my family’s new house in San Jose.

It was my first time living in a major metro since I was about 5, and I was soon riding my bike all over west San Jose, in the afternoons, and working at a local Pizza Hut in the evenings. BMX freestyle was tiny then. I knew there was a hardcore group of riders around the Bay Area, but I didn’t know how to find them. In those pre-internet days, you couldn’t look up people in obscure cultures and connect with them, like you can now. So I decided to actually publish a zine about BMX freestyle. I still hadn’t actually seen a real zine, I’d just heard about them in FREESTYLIN’, several months before.

I took some photos from riding in Boise, and from a trip I went on with my freestyle teammate, Jay Bickel, and his parents, to a contest in Venice Beach, California, that summer. I bought an old, manual, Royal typewriter for $15, at the San Jose swap meet. I laid out my zine on six sheets of typing paper, with photos and bits of text, Scotch-taped in place, for the layout. My first issue if San Jose Stylin’ zine, was three sheets of paper, with words and photos photocopied on both sides. Each copy was stapled in the top left corner, like a test in school. I didn’t realize that I was supposed to fold the sheets in half, like a little book. I made about 20 or 25 copies, and put 3 or 4 each in several local bikes shops that carried BMX bikes. My name and home phone number was in the zine. It was one of the first creative projects I ever did that took more than an hour. I spent several days working on that first zine, late at night, after coming home from Pizza Hut, wired from drinking 12 cups of Pepsi or Mountain Dew, on my shift.

After about a week, I got a phone call as we were sitting down to eat supper. It was a freestyler from the other side of San Jose, a guy named John Vasquez. He saw my zine, and invited me to come ride with him and his trick team crew. They had a quarterpipe. I was stoked. They were better riders than me, and I shot photos as we rode, hung out, and talked about freestyle. They told me about the Beach Park Ramp jam, put on once a month by Skyway pro Robert Peterson, up in Menlo Park. They also told me that Sunday afternoons were the time guys went up to The City, as locals called San Francisco, to ride in a certain spot in Golden Gate Park.

This was a zine pack that put out in early 2019. Two zines, 48 pages each, about The Spot in Redondo Beach, a legendary BMX freestyle scene location. Plus stickers and art flyers. These are the only zines I ever sold, and each set cost more tomake and ship than I charged for them.

Within a couple of weeks, I went to the Beach Park Ramp Jam, and met the guys from the Curb Dogs and the Skyway factory team, and handed them all zines. I was not only meeting, but hanging out all afternoon, and riding with, some of the pros, and really good amateurs, that I had been reading about in the magazines. That was pretty mind blowing, as a kid who grew up in small towns in Ohio, New Mexico, and Idaho. Where I grew up, we didn’t meet people who were in magazines. When I handed those guys my zine, they all said something like, “This is cool. When’s the next one coming out?” My reply was, “Uh… next one?” Suddenly I wasn’t just the new kid from Idaho, I was the “zine guy,” covering the Bay Area freestyle scene, which was probably the most cohesive BMX freestyle scene in the country then.

In the months that followed, I interviewed Dave Vanderspek, Maurice Meyer, Robert Peterson, Hugo Gonzalez, Rick Allison, and several other riders. I sent my zines to the editors at the real BMX magazines, and traded with other BMX zine publishers across the country, when I went to contests. Much to my surprise, and everyone else’s, my zine wound up landing me a job at Wizard Publications, home of BMX Action and FREESTYLIN’ magazines, a year later. I DID NOT see that coming. I didn’t even dream about it. I was trying to get really good and be a pro freestyler some day. The magazine offer just came out of left field. Suddenly I was in the BMX industry, and met and got to know all the other pro riders, and industry people, that I had been reading about in magazines for three years.

That only happened because I stopped daydreaming when I moved to San Jose. I buckled down, bought the equipment needed (see this post), and followed through on one of my “great ideas.” I published my first zine. Then I kept at it, and published 10 more issues of my zine. By the summer of 1986, I was making about $450 a month working at Pizza Hut, and spending $200 or more producing my zine, which had a snail mailing list of over 120 people by then. I took my creative ideas, and put in the actual work to produce a really ugly, but highly informative series of zines.

There are two points to this post. Everyone has cool ideas. Lots of people have great ideas, once in a while. But to make any progress creatively, you have to pick a good idea, and then do the actual work to make it happen. And keep doing that work, if it’s something ongoing, like a zine, a blog, a podcast, a YouTube channel, or anything similar. Daydreaming is great, pretty much everyone does it sometimes. But there’s a point as a creative person, early on, where you have to take action on your day dreams.

Start small. Do something challenging, but not huge. Push yourself a little bit, and finish a project that you weren’t sure if you could actually do. When you finish one project, look for another one, something a bit bigger, a bit more intense. Once you get used to actually finishing creative projects, time after time, a whole new world opens up. You begin to be known as a person who does this or does that, you have finished products to show other people. That leads to meeting other people, particularly other creative people, ones who also finish projects. You never know where that first project will ultimately lead.

My first zine, three sheets of paper stapled in the corner, led to a career in the industry I was most attracted to at the time. Here I am, over 38 years later, after self-publishing more than 1.5 million words, in zines, magazines, and blogs, writing about that first zine. Why? Because publishing my first zine turned me into someone who finishes creative projects, and not just a daydreamer. That step changes everything.